Political theory helps us make sense of how power works. It gives us the words to ask hard questions – like who should rule, what makes a government fair, and what freedom really means. These questions have been around for thousands of years. And they still matter now.

Most people hear political words every day – freedom, rights, equality, justice. But where do those ideas come from? And what do they actually mean?

This article breaks down 20 of the most important political theories. Some of them shape the systems we live under. Others challenge those systems. From liberalism and socialism to anarchism and realism, these theories explain the logic behind politics, even when politics looks messy or unpredictable.

If you’ve ever wondered why governments work the way they do – or why they fail – political theory is the place to start. It doesn’t tell you what to think. But it helps you understand what’s being said, what’s being done, and why it matters.

Definition of Political Theory

Political theory – also called political philosophy – is the systematic, analytical study of ideas about power, governance, justice, rights, and the state. It investigates how societies ought to be organized, why governments hold legitimate authority, and which principles best promote freedom, equality, and the common good. By evaluating classic texts and contemporary debates, political theory supplies the conceptual framework that guides political science research and shapes real-world policy.

The Biggest Political Theories

Liberalism

Core idea: Politics should protect and enlarge the freedom of the individual.

Key principles

-

Rule of law & constitutionalism: government’s powers are spelled out and limited.

-

Equal civil rights: speech, religion, press, property, due-process.

-

Free-market preference: economic exchange left largely to private actors, assuming competition keeps power in check.

-

Toleration & pluralism: society is a mosaic of differing world-views that must peacefully coexist.

Origins & thinkers: John Locke (natural rights), Adam Smith (market liberalism), J.S. Mill (liberty & harm principle).

Variations: -

Classical (night-watchman state, laissez-faire).

-

Social/modern (adds welfare safety-net so freedom is meaningful for all).

Contrasts: Opposes collectivist systems that sacrifice liberty to group goals; differs from conservatism by treating change as potentially liberating rather than threatening.

Conservatism

Core idea: Sudden, sweeping change often harms the fragile social fabric; preserve time-tested institutions.

Key principles

-

Tradition & continuity: customs encode hard-won wisdom.

-

Skepticism of rational redesign: society is too complex to be re-engineered overnight.

-

Hierarchical but reciprocal order: duties flow both up and down social ranks.

-

Pragmatic reform: change, when needed, should be incremental.

Origins & thinkers: Edmund Burke’s critique of the French Revolution; later strands include cultural (Oakeshott), free-market (Hayek), and religious conservatism.

Variations: -

One-nation/Tory (accepts some social welfare to maintain cohesion).

-

Libertarian-leaning (focuses on market tradition, less on moral order).

Contrasts: Shares free-market instincts with classical liberalism but parts company on social issues; rejects radical egalitarian or revolutionary schemes.

Socialism

Core idea: Major economic resources should be collectively owned and run for the common good, not private profit.

Key principles

-

Social and economic equality: narrow the gap between rich and poor.

-

Democratic or public ownership: factories, utilities, natural resources held by the people (via the state, co-ops, or communes).

-

Planning or strong regulation: steer production toward social needs (health, housing, education).

Origins & thinkers: Early utopians (Owen), scientific socialism (Marx & Engels), democratic socialists (Bernstein), modern social democrats (Bernie Sanders types).

Variations: -

Democratic socialism: ballots, not barricades; accepts markets for non-essential goods.

-

State socialism: extensive public sector alongside political centralisation.

Contrasts: Differs from liberalism on property, and from Marxism on methods (reform vs. revolution).

Marxism

Core idea: History is driven by class struggle; capitalism will inevitably give way to a classless, stateless communism.

Key principles

-

Historical materialism: economic structure shapes politics, law, culture.

-

Surplus value & exploitation: capitalists extract profit from workers’ unpaid labor.

-

Revolutionary praxis: the proletariat must seize the means of production.

-

Dictatorship of the proletariat (transitional state): dismantles old class apparatus before “withering away.”

Origins & thinkers: Karl Marx & Friedrich Engels (1840s-80s); later elaborated by Lenin, Gramsci, Rosa Luxemburg.

Variations: -

Leninism: vanguard party leads revolution.

-

Western Marxism: cultural superstructure (Gramsci, Frankfurt School).

Contrasts: Shares egalitarian goal with socialism but insists reform cannot overcome capitalist logic; fiercely opposes liberal individualism and conservative hierarchy.

Anarchism

Core idea: Coercive hierarchies—including the state—are unnecessary and harmful; society can organise through voluntary cooperation.

Key principles

-

Decentralisation: decisions made in local assemblies, federated only where needed.

-

Mutual aid: people thrive by helping one another, not competing.

-

Direct action: strikes, occupations, cooperatives rather than electoral politics.

Origins & thinkers: Pierre-J. Proudhon (“property is theft”), Mikhail Bakunin (collective freedom), Emma Goldman (anarcha-feminism), Peter Kropotkin (scientific mutual aid).

Variations: -

Anarcho-communism (common ownership, gift economy).

-

Anarcho-syndicalism (worker unions run production).

-

Anarcho-capitalism (private property plus stateless markets).

Contrasts: Rejects the state unlike socialism/Marxism; differs from libertarianism by distrusting private hierarchies too.

Fascism

Core idea: The nation (or race) is an organic whole that must be unified under a supreme leader, using force and ritual to conquer decadence and enemies.

Key principles

-

Ultra-nationalism & mythic past: destiny of the chosen people.

-

Authoritarian leadership: charismatic dictator embodies the nation’s will.

-

State-directed economy: private ownership allowed but subordinated to state goals (corporatism).

-

Militarism & mass mobilisation: rallies, uniforms, youth leagues forge unity.

Origins & examples: Mussolini’s Italy (1922-45), Nazi Germany, Falangist Spain; modern neo-fascist movements echo themes.

Contrasts: Rejects liberal pluralism, socialist equality, and conservative gradualism alike; differs from communism in glorifying nation over class.

Libertarianism

Core idea: Individual freedom—especially property rights and free exchange—should be restrained only to prevent force or fraud.

Key principles

-

Non-aggression principle: no one may initiate violence or coercion.

-

Minimal state (“night-watchman”): police, courts, sometimes defense—nothing more.

-

Free markets & voluntary contracts: capitalism without regulatory or redistributive layers.

-

Self-ownership: people own their bodies; personal lifestyle choices off-limits to government.

Origins & thinkers: Classical liberals (Locke), laissez-faire economists (Mises, Hayek), neo-libertarians (Robert Nozick, Murray Rothbard).

Variations: -

Minarchism (minimal state).

-

Anarcho-capitalism (no state at all, pure private law).

Contrasts: Overlaps with liberalism on civil liberties but rejects welfare-state liberalism; opposes conservative moral legislation; at odds with socialism on property.

Utilitarianism

Core idea: The morally right policy maximises overall happiness or utility—every person’s welfare counts equally.

Key principles

-

Consequentialism: only outcomes, not motives or rules, settle right vs. wrong.

-

Greatest-happiness calculus: add up pleasures and pains (in practice, use proxies like health, income, satisfaction).

-

Impartiality: my pleasure is no more valuable than yours.

Origins & thinkers: Jeremy Bentham (felicific calculus), John Stuart Mill (qualitative pleasures), modern cost-benefit analysis.

Applications: public-health triage, climate policy, animal welfare debates.

Critiques: hard to measure utility; may justify sacrificing minorities; overlooks rights-based constraints.

Contrasts: Provides a decision-tool used by liberals, socialists, and conservatives alike; differs from deontological theories that rank duties higher than outcomes.

Realism (International Relations)

Core idea: In an anarchic world with no global sovereign, states pursue survival and power; moral rhetoric masks self-interest.

Key principles

-

Anarchy: absence of a world government forces self-help.

-

Power & security: military and economic capabilities are the currency.

-

Balance of power: coalitions form to check rising hegemons.

-

Rational but pessimistic: cooperation is possible yet fragile.

Origins & thinkers: Thucydides (Melian Dialogue), Niccolò Machiavelli, modern founders Hans Morgenthau, Kenneth Waltz (structural realism).

Variations: -

Classical realism (human nature drives power-lust).

-

Neorealism (system structure drives behavior).

Contrasts: Counters liberal internationalism (institutions tame anarchy) and constructivism (ideas shape interests); stands apart from nationalism by treating national identity as a tool, not an end.

Nationalism

Core idea: A people who share language, culture, or history deserve self-government within their own sovereign state.

Key principles

-

Nation-state ideal: political borders should match cultural boundaries.

-

Self-determination: legitimacy flows from the nation’s will, not dynastic or imperial claims.

-

Emotional solidarity: symbols, myths, and rituals forge unity.

Origins & milestones: French Revolution, 19th-century unifications (Italy, Germany), anti-colonial movements.

Variations: -

Civic nationalism (membership by citizenship and shared values).

-

Ethnic nationalism (membership by ancestry and heritage).

-

Expansionist/irredentist strands can shade into chauvinism.

Contrasts: Can dovetail with liberal democracy (civic) or clash violently with it (ethnic). Differs from realism—which sees nationhood as one power factor—and from cosmopolitan liberalism, which downplays national borders.

Feminist Political Theory

Core idea: Power is gendered. Laws, economies, and cultures have been built around male norms; justice requires exposing and dismantling that bias so everyone, of every gender, can flourish.

Key principles

-

Patriarchy critique: social, legal, and economic rules systematically privilege men.

-

Intersectionality: gender meets race, class, sexuality, disability; oppression is layered, not single-issue.

-

Embodied experience: personal stories (e.g., care work, reproductive rights) reveal hidden power relations.

Origins & thinkers: Mary Wollstonecraft’s demand for women’s citizenship (1792); first-wave suffragists; Simone de Beauvoir (second wave); bell hooks and Kimberlé Crenshaw (intersectional / third wave).

Variations: -

Liberal feminism (equal legal rights).

-

Radical feminism (patriarchy embedded in every institution).

-

Eco-feminism (links women’s subordination to exploitation of nature).

Contrasts: Shares equality aim with Rawlsian justice but spotlights gender; differs from communitarianism by challenging, not celebrating, traditional norms.

Environmentalism / Green Politics

Core idea: A viable society must operate within ecological limits and consider the welfare of future generations as seriously as today’s voters.

Key principles

-

Sustainability: meet present needs without crippling the planet’s life-support systems.

-

Precautionary principle: when environmental harm is plausible, err on the side of restraint.

-

Intergenerational & interspecies justice: moral circle extends to the unborn and to non-human life.

Origins & thinkers: Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962); the Club of Rome’s Limits to Growth; political greens in 1970s Germany and beyond.

Variations: -

Deep ecology (intrinsic value of nature).

-

Eco-socialism (links ecological crisis to capitalist growth logic).

-

Market environmentalism (carbon pricing, green tech innovation).

Contrasts: Challenges neoliberal growth orthodoxy; allies with communitarianism on local resilience; pushes realism in IR to treat climate as a security threat.

Communitarianism

Core idea: Individuals are shaped by—and owe duties to—the communities that give their lives meaning; hyper-individualist politics erodes the common good.

Key principles

-

Shared moral culture: virtues like trust and solidarity require collective upkeep.

-

Civic responsibility: rights make sense only alongside duties.

-

Contextual self: identity is rooted in family, neighborhood, tradition.

Origins & thinkers: Alasdair MacIntyre (After Virtue), Michael Sandel, Charles Taylor in the 1980s “liberalism vs. communitarianism” debate.

Variations: -

Responsive communitarianism (Etzioni) seeks balance: strong civil society plus liberal rights.

-

Religious communitarianism (Catholic social teaching, Confucian revival).

Contrasts: Disputes Rawls’s abstract “veil of ignorance”; closer to conservatism on social roots, but more open to state action than libertarianism.

Neoliberalism

Core idea: Free markets, private property, and global trade unleash innovation and growth; the state should set rules then step back.

Key principles

-

Deregulation: remove barriers to competition.

-

Privatisation: shift public services into profit-seeking firms.

-

Fiscal restraint: low taxes and limited welfare to avoid “crowding out” enterprise.

-

Globalisation: free movement of capital, goods, and (sometimes) labour.

Origins & thinkers: Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman; implemented by Thatcher (UK) and Reagan (US) in the 1980s; spread via IMF/World Bank “Washington Consensus.”

Variations: -

Ordoliberalism (German strand—strong antitrust rules).

-

Third-way/market-friendly social democracy (Clinton, Blair).

Contrasts: Shares market faith with libertarianism but keeps a managerial state; opposed by eco-politics and post-colonial critics who see new forms of dependency.

Post-Colonial Theory

Core idea: Formal independence did not erase colonial power; language, knowledge, and economic ties still marginalise formerly colonised peoples.

Key principles

-

Subaltern voices: foreground perspectives normally silenced by Euro-centric narratives.

-

Hybridity & identity: cultures are mixed, resisting neat colonial categories.

-

Decolonisation of mind: challenge imported norms in education, law, art.

Origins & thinkers: Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth (1961); Edward Said’s Orientalism (1978); Gayatri Spivak (“Can the Subaltern Speak?”).

Variations: -

Indigenous resurgence movements.

-

Afro-futurism as cultural critique.

Contrasts: Extends critical theory’s ideology critique to global North–South dynamics; skeptical of neoliberal “development” scripts.

Critical Theory

Core idea: Culture, media, and ideology subtly reproduce domination; critique should expose those patterns and empower emancipation.

Key principles

-

Ideology critique: common-sense ideas often serve ruling interests.

-

Dialectical method: social facts are contradictory and changeable.

-

Emancipatory knowledge: theory must help people act against oppression.

Origins & thinkers: Frankfurt School (Horkheimer, Adorno, Marcuse) fleeing 1930s fascism; later Jürgen Habermas (communicative action).

Variations: -

Cultural studies (Stuart Hall).

-

Critical race theory (Derrick Bell, Kimberlé Crenshaw).

Contrasts: Shares Marxist roots but widens focus beyond economic class; differs from realist pragmatism by insisting that “facts” are value-laden.

Structuralism / Post-Structuralism

Core idea: Meaning and identity arise from underlying structures (language, myths, discourses) rather than isolated agents; power works through these codes.

Key principles

-

Structure over subject: society is a system of signs.

-

Binary oppositions: concepts gain sense only in contrast (e.g., male/female).

-

Deconstruction (post-structural): reveal internal contradictions, celebrate plurality.

Origins & thinkers: Structural linguistics (Saussure); anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss; then Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida, Judith Butler tearing structures apart.

Applications: gender performativity, media framing, legal text interpretation.

Contrasts: Challenges human-nature assumptions in liberalism/realism; supplies analytic tools for feminist and post-colonial critiques, but frustrates communitarians who seek stable shared meanings.

Rawlsian Liberal Egalitarianism

Core idea: A just society is the one free, rational people would design if they did not know whether they would be rich or poor, privileged or disadvantaged.

Key principles

-

Veil of ignorance: strips away bias.

-

Two principles of justice: equal basic liberties; social-economic inequalities allowed only if they benefit the least advantaged (the “difference principle”).

-

Fair equality of opportunity: jobs and offices open to all under genuine, not just formal, competition.

Origins & thinker: John Rawls, A Theory of Justice (1971); revived normative political philosophy.

Debates & variations: -

Luck egalitarianism asks to neutralise brute luck further.

-

Political liberalism (Rawls later) focuses on consensus among plural world-views.

Contrasts: Bridges liberal rights and socialist equality; criticised by libertarians (redistribution coerces) and communitarians (too abstract).

Deliberative Democracy

Core idea: What makes laws legitimate is not just the count of votes but the quality of public reasoning that precedes them.

Key principles

-

Reason-giving: participants must justify positions with arguments others could accept.

-

Equality & inclusion: every affected person gets a voice; barriers of status, wealth, and identity are minimised.

-

Transformative dialogue: listening may change minds, not just aggregate preferences.

Origins & thinkers: Jürgen Habermas’s “public sphere”; Joshua Cohen, Amy Gutmann & Dennis Thompson in the 1990s; practiced in citizens’ juries, deliberative polls, Iceland’s 2010 crowdsourced constitution draft.

Variations: -

Mini-publics (small, representative forums).

-

Online deliberation platforms.

Contrasts: Supplements electoral democracy criticised by technocracy for ignorance, but resists technocracy’s expert-only rule by insisting on lay input.

Technocracy

Core idea: Complex, high-stakes decisions (monetary policy, pandemic response, climate engineering) should be steered by credentialed experts using the best available evidence, insulated from short-term political pressures.

Key principles

-

Meritocratic selection: scientific competence over electoral popularity.

-

Evidence-based policy: data models, cost–benefit analysis, scenario planning.

-

Insulation mechanisms: independent central banks, expert regulatory agencies.

Origins & practice: early 20th-century progressive engineers; modern examples include the U.S. Federal Reserve, EU Commission, Singapore’s civil service.

Critiques & variations: -

Democratic technocracy (experts propose, citizens dispose).

-

Concerns about accountability, elitism, and tunnel vision (e.g., 2008 financial crisis).

Contrasts: Opposite pole to populism; overlaps with utilitarianism’s optimisation but clashes with deliberative democracy’s lay participation and communitarian calls for local wisdom.

The Biggest Political Thought Traditions

While the 20 theories above represent some of the most influential frameworks in modern political thinking, they belong to a much broader and older intellectual tradition. Political thought stretches across civilizations, centuries, and cultures—shaped by philosophers, revolutionaries, theologians, and critics responding to the challenges of their time.

Below, we’ve organized major traditions and schools of political thought into eight thematic categories. These groupings help readers place individual theories—such as liberalism, anarchism, or post-colonialism—within their wider historical and philosophical context. From ancient foundations to contemporary global perspectives, this overview offers a structured guide to how political ideas have developed, diverged, and endured.

1. Classical & Non-Western Foundations

-

Platonism – the just polis ruled by philosopher-kings (Republic).

-

Aristotelianism – politics as the telos-oriented pursuit of the “good life” in the polis (Politics).

-

Stoicism – cosmopolis, natural law, and universal citizenship (e.g., Cicero, Epictetus).

-

Mohism – early Chinese plea for impartial “universal love” and meritocratic rule.

-

Confucian Political Thought – hierarchical yet virtue-based governance through li and ren.

-

Legalism (Fajia) – centralized authority legitimised by clear, impersonal law (Han Fei).

-

Roman Republicanism – mixed constitution, civic virtue, res publica (Polybius, Cicero).

2. Medieval & Religious Traditions

-

Augustinianism – city of God vs. earthly city; political authority’s post-lapsarian role.

-

Thomistic / Scholastic Natural-Law Theory – state as instrument for common good, grounded in reason and divine law (Aquinas).

-

Islamic Political Philosophy – virtue politics (al-Farabi), cyclical sociology (Ibn Khaldūn).

-

Hebrew Theocratic Thought – covenantal legitimacy and prophetic critique of kings.

3. Early-Modern Currents (15th–18th c.)

-

Civic Humanism (Machiavellian Republicanism) – republican liberty and prudential statecraft.

-

Social-Contract Theories –

-

Hobbes: security via absolute sovereign.

-

Locke: natural rights, limited government, right of resistance.

-

Rousseau: general will and popular sovereignty.

-

-

Classical Liberalism – individual liberty, private property, limited state (Locke, Smith).

-

Mercantilism & Cameralism – state-managed economic growth as raison d’état.

-

Utilitarianism – “greatest happiness” metric for legislation (Bentham, J. S. Mill).

4. Nineteenth-Century Ideologies

-

Conservatism – Burkean traditionalism, organic social change.

-

Romantic Nationalism – nation as cultural-historical organism.

-

Positivism – scientific re-engineering of society (Comte).

-

Utopian Socialism – Owen, Fourier, Saint-Simon.

-

Marxism / Scientific Socialism – class struggle, historical materialism.

-

Anarchism – Proudhon (mutualist), Bakunin (collectivist), Kropotkin (communist), Stirner (egoist).

-

Fabian Socialism – gradual, parliamentary reform (Webbs).

-

Classical Feminism – Wollstonecraft’s vindication of equal civic status.

5. Twentieth-Century & Contemporary Theories

Liberal & Democratic Extensions

-

Social Democracy – welfare-state compromise of capitalism and socialism.

-

Keynesianism – macro-economic steering for full employment.

-

Neoliberalism – competitive markets, deregulation, privatisation (Hayek, Friedman).

-

Libertarianism – minimal state, robust self-ownership (Nozick).

-

Rawlsian Liberal Egalitarianism – justice as fairness, veil of ignorance.

-

Communitarianism – social-embedded selves, civic virtue (MacIntyre, Sandel).

-

Deliberative Democracy – norm-guided public reasoning (Habermas).

Critical & Post-Structural Currents

-

Critical Theory – Frankfurt School critique of ideology, culture, capitalism.

-

Structuralism / Post-Structuralism – power-knowledge networks (Foucault), deconstruction (Derrida).

-

Postmodernism – scepticism toward grand narratives (Lyotard).

Identity & Liberation Frameworks

-

Second- & Third-Wave Feminist Theories – liberal, radical, intersectional, eco-feminism.

-

Queer Political Theory – contesting heteronormativity in law and citizenship.

-

Intersectionality – overlapping systems of oppression (Crenshaw).

-

Post-Colonial Theory – colonial power, subaltern agency (Said, Fanon, Spivak).

-

Indigenous Political Thought – sovereignty and relational land ethics.

-

Dependency Theory / World-Systems – core–periphery extraction (Prebisch, Wallerstein).

-

Liberation Theology – Christian praxis for social justice (Gutiérrez).

Green & Tech-Centric Ideas

-

Environmentalism / Green Political Theory – sustainability, ecological citizenship.

-

Deep Ecology & Eco-Socialism – intrinsic value of nature; socio-ecological class analysis.

-

Cyber-Libertarianism & Digital Governance – internet as free sphere beyond states.

6. Authoritarian, Totalitarian & Technocratic Models

-

Machiavellianism – amoral pursuit of power.

-

Political Realism – interest-based, power-centric view of politics and IR.

-

Fascism (and Nazism) – ultra-nationalism, corporatist state, charismatic ruler.

-

Leninism / Stalinism / Maoism – revolutionary vanguard, one-party rule, planned economy.

-

Bonapartism & Caesarism – personalist authoritarianism claiming popular mandate.

-

Technocracy – governance by technical experts.

-

Totalitarianism – state control over every aspect of life (Arendt).

7. Theories of International Relations

-

Classical & Neo-Realism – anarchy, balance of power, security dilemma.

-

Liberal Institutionalism – regimes and interdependence mitigate anarchy.

-

English School – international society and common rules.

-

Marxist / Neo-Gramscian IR – transnational class and hegemony.

-

Constructivism – socially constructed state interests (Wendt).

-

Feminist & Post-Colonial IR – gendered and imperial structures of world politics.

-

Green IR – ecological limits and global commons.

Cross-Cutting Conceptual Tools

-

Legitimacy & Authority – what makes power rightful? (Weber, Beetham).

-

Ideology Critique – how belief systems sustain power (Mannheim, Žižek).

-

Biopolitics & Governmentality – life-administering power (Foucault).

-

Populism – appeal to “the people” against elites; left- and right-wing variants.

Political Theory vs. Practice: Does It Ever Match?

Political theories look clean on paper. They use logic. They draw lines between right and wrong. They offer blueprints for better government. But real politics is messy. People don’t always follow the script. And politicians rarely act like the theorists they quote.

In theory, democracy gives power to the people. In practice, lobbyists, donors, and party machines often shape what gets done. A politician might praise liberty or equality in a speech, but vote for laws that limit both. Leaders use words like “freedom” or “justice,” but they don’t always mean the same thing every time. That gap between talk and action is one reason people lose trust.

Still, that doesn’t mean political theory is useless. Most systems we live under are built on some idea—often borrowed straight from philosophy. The U.S. Constitution is grounded in Enlightenment thought. The welfare state has roots in socialist theory. Free markets follow principles found in classical liberalism. Even authoritarian regimes often claim to follow some “higher” idea – law, order, national unity.

So yes, theory matters. But it rarely shows up in full. What we get is a mix—part principle, part compromise, part power struggle.

People live with that tension every day. A law may reflect a noble goal, but still fall short in practice. A party might campaign on one set of ideas, then govern with another. This is not always due to bad faith. Sometimes it’s the cost of negotiation, or the weight of reality.

Political theories can’t predict every outcome. But they offer something else. They give people a way to judge what’s happening. They help explain why some policies feel fair and others don’t. They also give people language to push back, to argue for change, or to defend what they believe in.

So while no government is a perfect model of any one political philosophy, knowing the theories still helps. It makes the difference between watching politics happen and understanding why it happens the way it does.

In the end, theory gives us ideals. Practice gives us the test.

Read also

The Most Popular on BitGlint

Top 100 Personal Items List

Everyone uses personal items in their daily lives, often without even thinking about them. From the moment you wake up...

30 Vice Versa Examples & Meaning

The phrase vice versa is short, but it carries a lot of meaning. You’ve probably heard it in daily conversations, read...

Top 30 Desire Examples & Definition

Desire is a powerful force that drives much of human behavior, shaping our goals, dreams, and everyday decisions. It's...

100 Non-Digital Things List

In everyday life, there are still hundreds of objects, tools, and materials that exist completely outside the digital...

30 Examples of Attention & Definition

Have you ever noticed how a catchy tune can grab your attention, even when you're busy doing something else? It's...

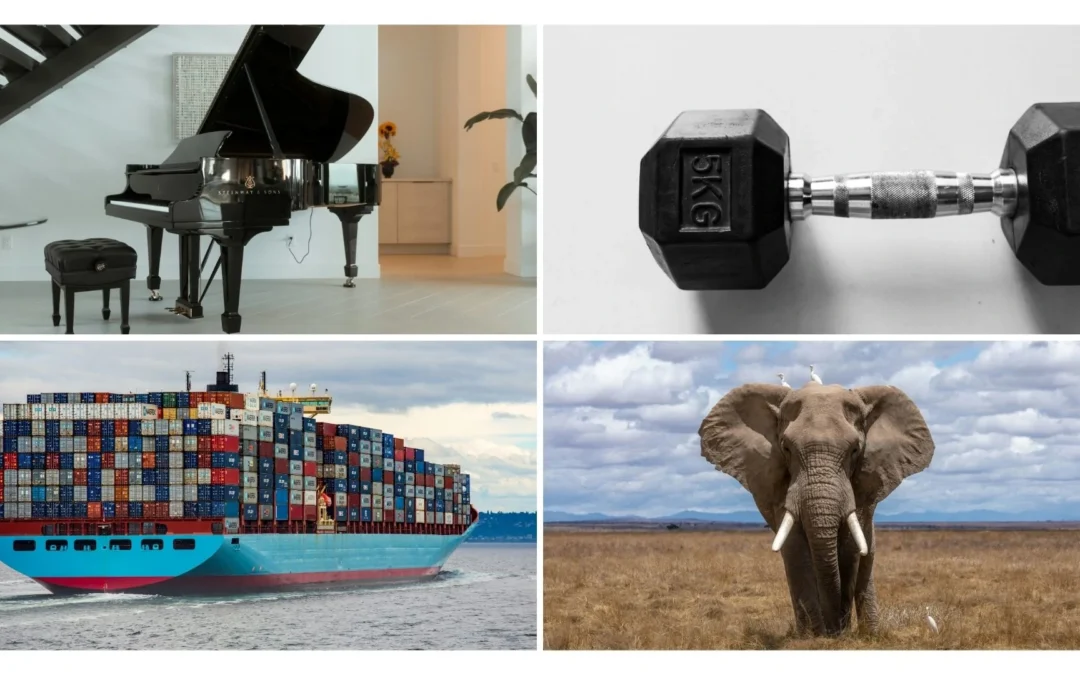

100 Heavy Things List

Some things in life are just heavy. You know it when you try to lift them. It could be a steel beam, a couch, a full...

Top 30 Intimacy Examples & Meaning

Intimacy goes beyond physical touch or romantic moments. It’s about closeness, trust, and connection. In everyday...

Get Inspired with BitGlint

The Latest

30 Longevity Examples & Meaning

Longevity is a word we hear often, but few stop to think about what it really means. Most people connect it with a long life. But longevity is more than just the number of years someone lives. It also applies to things that last—ideas, traditions, relationships,...

30 Teasing Examples & Definition

Teasing is a common part of human interaction. People tease in different ways, for different reasons. Sometimes it is friendly. Sometimes it can hurt feelings. Understanding what teasing means and seeing clear examples helps everyone handle these moments better....

30 Doubt Examples & Meaning

Everyone experiences doubt. It can show up in small everyday choices or big life decisions. Sometimes it’s a quiet pause. Other times, it can feel overwhelming. You might doubt your actions, your thoughts, or even yourself. But what is doubt, really? Why does it...

30 Biotechnology Examples in Everyday Life

Biotechnology is a part of everyday life, even if most people don’t notice it. It plays a role in the food we eat, the medicines we take, and even how diseases are treated. From life-saving vaccines to better crop production, biotechnology is shaping the way we live....